What Is Called the Art and Science of Leadership

Simply one final stronghold stands in the style of Roman victory and the promise of peace throughout the empire.

These words appear on-screen in the opening scene of the picture Gladiator. Soldiers are lining up for battle against the barbarian tribes in Germania. Russell Crowe's character, Roman Gen. Maximus Decimus Meridius, walks along the ranks of the army. The soldiers rise equally he approaches, looking at him with respect and adoration. Maximus seems calm and determined equally he commands, "At my signal, unleash hell."

At this disquisitional moment, in this pivotal battle, Maximus moves on to lead the dangerous and decisive part of the tactical maneuver behind enemy lines. In the forest where the cavalry await him, he inspires backbone in his men by validating the indelible legacy of their actions that twenty-four hour period, linking past, present, and futurity. "Brothers, what nosotros do in life echoes in eternity."

The military leader, the commander, is a central figure in our common narratives about state of war. Gladiator is just one of a big number of popular movies and books that center on great armed services leaders. Merely there is a surprising dearth of contemporary bookish emphasis on military machine leadership theory. Recently, I looked through the abstracts of manufactures published over the last five years in three international scientific journals on military studies (ii of which were ranked in the top 20 armed forces studies publications on Google Scholar). Interestingly, I found very few articles related to theorizing on military machine leadership—i.east., articles that deal with how to understand, anticipate, or develop military leadership from a theoretical perspective. While a multiplicity of scientific books and articles are concerned with general leadership and management, it seems from this choice of articles that academic attention towards military leadership is rather more scarce. In this selection of articles, military leadership was almost frequently embedded in other central themes such as combat motivation, military operations, unit cohesion, or soldier values and identities. Apparently, literature on military leadership virtually often takes the course of personal accounts by military machine officers, for instance, or historical monographs about peachy war machine leaders, battles, and wartime strategies.

We might wonder why this is the case. Why are military studies, as a scholarly discipline, non more concerned with theorizing on military leadership? In part this is because in the past, books and theories on leadership just were books on war machine leadership. There was no demand to stress the military part; this went without maxim. Merely in the terminal century, with industrial social club in the ascent, the expansion of the public sector, and the upsurge in big, multinational private companies, theories on leadership developed to await far beyond the battlefield.

It is characteristic of war machine leadership and civic leadership akin that their primary aim is not noesis development in itself but rather the use of cognition. Theories on military leadership are mainly interesting for the military profession insofar every bit they are able to contribute, for case, to analysis, controlling processes, command practice, recruitment, or training. Other professional fields, such as police force work or nursing, are as well characterized by this intertwinement of theory and do. Nonetheless, the development of noesis is essential to the practice of military leadership, not least because the faces of state of war, disharmonize, stabilization, and peace are continuously changing.

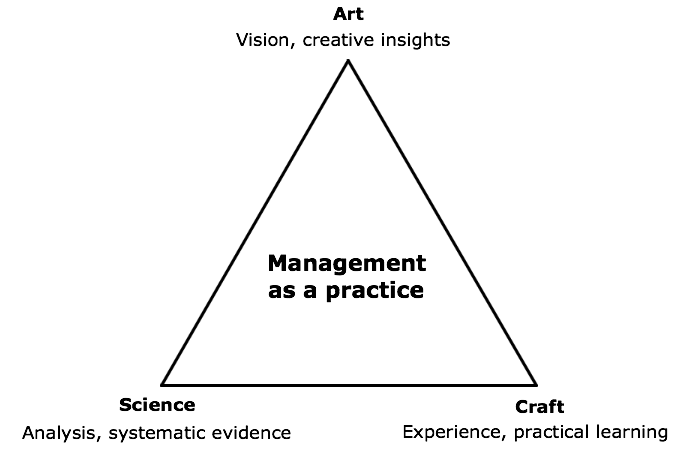

I recently re-read the book Managing past Canadian professor of management studies Henry Mintzberg. In information technology, Mintzberg farther develops thoughts from a previous book, Managers Not MBAs. He suggests that the practice and styles of management can exist visualized as a triangle whose three corners correspond management as an art, as a craft, and as informed by science.

Credit: Henry Mintzberg, Managing

Management equally an fine art is related to the demand for managers to be visionary and creative. They need to have ideas and exist able to synthesize and integrate diverse interests and viewpoints. Management as a arts and crafts is related to the practical conquering and use of knowledge in its relevant context. The scientific contribution to direction practices is the provision of society and pregnant through systematic analysis of practice, experience, and assumed knowledge. The indicate of the triangle representation is to put various conceptions into perspective and so that we can more easily come across what each of them accentuates and what they button into the background.

While reading the volume, Mintzberg's three management categories seemed somehow familiar to me. I recognized their relevance from discussions that I had had with colleagues in the Danish military. I realized that sometimes when ideas, expectations, or suggestions collide, information technology is merely because nosotros think differently most war machine leadership; considering our conceptual images of what military leadership is differ. The indicate is that how we perceive military machine leadership—every bit an art, craft, or scientific discipline—frames our perceptions of how leaders should pb in practise. It influences our judgments and priorities. The perception of armed forces leadership as an art might lead usa to emphasize the training of talented individuals and brand the states encourage the establishment of educational and organizational structures that eye on individual career evolution. This perception of military leadership is popular in everyday narratives and pictures—movies, books, and the similar. In these narratives the war machine leader is a fundamental determinant of success or failure in a given military campaign. While this perspective might contribute to more creativity, sensitivity, intuition, and out-of-the-box thinking in military machine organizations, it may too favor individualism and glorification of individuals at the expense of acknowledging the importance of commonage efforts.

The view of military leadership as a craft relies first and foremost on applied experience. This perspective might favor the blueprint of war machine didactics and organizational structures that support professional development through tangible experience and experience-sharing. The view of military leadership as a craft might as well brand u.s.a. more prone to emphasize the development of operational tools such every bit military doctrines and standard operating procedures. In its archetype, the thought of military leadership as a craft might emphasize leaders' ain (express) experience to the exclusion of ideas and theories that come from outside of the military machine profession. This has been called the "Not Invented Here" effect.

From the scientific discipline-centric perspective, the idea of observation of and reflection on individual and organizational do is pivotal to the quality and development of military machine leadership. The scientific perspective might to a greater caste encourage the invitation of other disciplines—folklore, cultural studies, general leadership theory, etc.—to inform and develop the practice of military leadership. On the downside of the scientific perspective, we might point to the mushrooming of management technologies such as Primal Functioning Indicators, Counterbalanced Scorecard, risk management systems, operation reviews, time-tracking templates, and cess systems that permeate many organizations today. While each of these technologies might exist helpful in their specific purpose, it seems in their totality that instead of helping leaders to manage, they are often managing the leaders.

Mintzberg's message is not that the three categories are mutually exclusive. On the opposite, he argues that useful managing or leadership should combine all 3 without whatsoever ane of them being completely ascendant. Each category accentuates some aspects of the phenomenon of leadership while pushing other aspects into the background. In view of this reflection on Mintzberg's categories, the following two suggestions might be offered:

one. Encourage a plurality of perspectives on military leadership.

The employ of Mintzberg's three leadership categories illustrates how an awareness of unlike perspectives will enrich our agreement of armed services leadership. The field of war machine studies should invite everybody interested to participate in a continuous and open up-minded dialogue with the aim of exploring existing and new perspectives that may further enhance military leadership development. This dialogue implies abandoning categories of "right" and "wrong." This approach may be especially opposed in military organizations, which are highly hierarchical and which often teach their members to strive for precision and certainty and inherently prioritize the ability to answer questions over asking them. A concerted try should exist fabricated, however, to overcome this opposition and enrich the military's own theoretical approach to leadership.

2. Encourage military leaders to reverberate on what categories and perspectives they apply in their own leadership approaches.

Our views often remain unquestioned until confronted with different ones. Being aware of our own ingrained perspectives on leadership and being attentive to those of others will make framing and making decisions clearer, and volition enhance mutual understanding and cooperation. Furthermore, this caste of self-sensation makes it easier to realize when an upshot of discussion may be related to deeply rooted perspectives and their concomitant expectations and values.

The military machine profession and war machine scholars should appoint in a new, explorative dialogue. Instead of discussing normative, instrumental definitions of "good armed services leadership," we should start to think in terms of those performative background perspectives that in reality shape our ain definitions of military leadership. In 1986, Gareth Morgan wrote his acknowledged book Images of Organization. In it, Morgan unveils the concept of organization through the utilize of eight metaphors (organizations as machines, as organisms, as political systems, etc.). He demonstrates how each of these eight images of organisation leads united states of america to sympathise and administer organizations in a specific, pre-framed style. If our thinking about organizations is based simply in one metaphor, we cannot empathize reasoning and discourse based within others. The same might be said nigh leadership perspectives. In order to identify and refine military leadership best practices, we need to unfold a plurality of images. If we stick to the heroic ethics of Gladiator and the art perspective, in which leadership competencies are seen equally innate, we neglect to appreciate two cadre elements of leadership: that leading is relational—it happens between people—and that leading is shaped by the context in which information technology happens. New challenges military leaders volition face will crave appropriate leadership techniques. Only when we engage openly on the multiple perspectives that inform armed services leadership theory will those techniques emerge in practice.

Image credit: Sgt. April Campbell, U.s. Army

Source: https://mwi.usma.edu/art-craft-science-think-military-leadership/

0 Response to "What Is Called the Art and Science of Leadership"

Post a Comment